Gazprom — national treasure?

In 2018 Gazprom only paid 13% of its profits to the federal budget of the Russian Federation. The remaining 87% went to its own management or to its investment projects. The revenues of Gazprom’s executives and members of its board of directors in 2018 amounted to 4.312 billion rubles. In 2018 there were 16 people on Gazprom’s board. However, in the first quarter of 2019 alone the company received 921 million euros (approximately 69 billion rubles) just in loans from several consortia of banks.

‘Gazprom holds the world’s largest natural gas reserves. The Company’s share in the global and Russian gas reserves amounts to 16 and 71 per cent respectively. As the world’s leading gas producer, Gazprom accounts for 12 per cent of the global gas output and 69 per cent of domestic gas production. At present, the Company is actively implementing large-scale gas development projects in the Yamal Peninsula, the Arctic shelf, Eastern Siberia and the Russian Far East, as well as a number of hydrocarbon exploration and production projects abroad.’ (see Gazprom’s website https://www.gazprom.ru/about/)

Gazprom derives its main income from production and sales of Russia’s national treasure — natural gas.

This national treasure is being mined and sold by Gazprom at a record, ever-increasing pace, but for some reason the state’s coffers remain closed to the citizens. Moreover, as Gazprom and its contractors grow richer, the number of poor people in Russia increases. There are about 20 million of them in the country now — over 13% of Russia’s total population. Official data based on Rosstat’s algorithm (called ‘monetary’ — in relation to subsistence rate) is, according to most experts, controversial, to put it mildly. Which begs the question: how is this possible?

The answer is a simple and sad one. Gas, oil, diamonds, and so on, have long become property of not the state, not the people who produce them, but of the officials who own both the state and its mineral resources, together with the labor force slaving away at them. Those entrusted with safeguarding strategic reserves of the motherland care primarily about their own well-being. And despite the fact that occasionally some top managers of state corporation go to jail as a result of under-the-carpet fighting between their own kind the majority of officials “watching” the public property remain immune from prosecution and, at the same time, oddly wealthy. The scandal around Arashukov family is no more than an exception which proves the rule.

It’s all the more interesting to look at Uraltransgaz, a subsidiary (not the richest or the most influential one) of Gazprom, and at its recent former executive Anatoly Naumeyko, his current fortune and that of his family members.

Uraltransgaz transports and distributes gas in Sverdlovsk, Chelyabinsk, Kurgan and Orenburg regions. The company runs 8,000 main gas transmittal pipelines and 18 compressor stations. Uraltransgaz builds and puts into operation new pipeline offshoots and stations, reconstructs existing facilities, and is also responsible for the safety of the gas transmission system. The most essential part of the enterprise includes 13 linear production departments of main gas pipelines, an engineering and technical center, a logistics department and a maintenance department called Energogazremont.

Every few years, this structure is shaken by large scandals. Alexander Kolesin, head of the company's legal department, managed to withdraw about 120 million rubles from the budget of Uraltransgaz from 2003 to 2006. This case was only brought to court in 2011 — after numerous corruption-related delays. Kolesin and his accomplice Valery Bogachev, owner of some debt recovery firms convicted in 2007 to six years in prison for extorting ten million dollars from general director of Uraltransgaz LLC, were each sentenced to nine years in prison.

A little earlier another deputy general director, Anatoly Naumeyko, suddenly left the company 2 years before planned retirement. He was also head of Energogazremont department which, as the name suggests, was a very important and profitable enterprise.

Anatoly Vasilevich Naumeyko was born on February 8, 1952 in the village of Priozerny, Tselinograd Region. He graduated from Ural Polytechnic Institute (1978) as civil engineer. Laureate of Gazprom Prize (1998), Cherepanov Prize (2000), Academic Advisor to RIA (2000). In 1978–1990 Naumeyko worked in the Ural Gas Engineering Inspectorate as inspector, then chief; in 1990–1995 Director of MP Agrogaz; from 1995 to 2009 he was Deputy General Director at Uraltransgaz and Head of Energogazremont department.

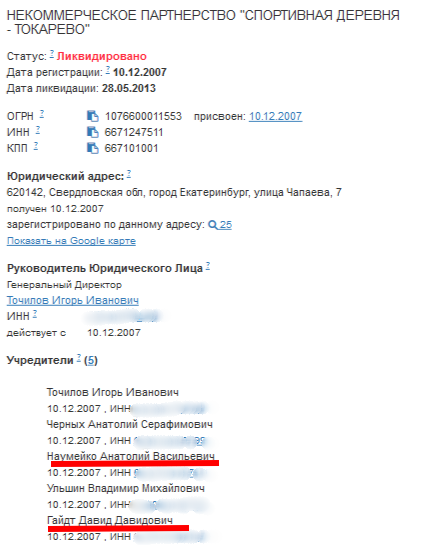

It is also interesting that while working with Gazprom Naumeyko registered himself as founder of a number of enterprises: Podryad (ООО “Подряд”) in 1991, Deko (ООО “Деко”) in 2006, and two companies in 2007 — Uromgaz-Irbit (ООО “Уромгаз-Ирбит”) with authorized capital of 45.5 million roubles and NPO Sportivnaya Derevnya Tokarevo (НП “Спортивная деревня Токарево”). In 2011 he acquired a stake in Neftegazservice, and much more.

Energogazremont has been liquidated, as well as other Naumeyko’s enterprises in Russian jurisdiction. Few people remember the Gazprom man himself, either. After all, right after the end of his service Anatoly Naumeyko chose Andorra as his permanent residence.

Andorra is a small independent principality located in the Pyrenees between France and Spain. It is a well-known duty-free zone that also attracts tourists with its ski resorts. In the capital of the state, the city of Andorra la Vella, there are many boutiques, jewelry stores and shopping centers. Due to high level of bank confidentiality, Andorra is a tax haven. At the same time it is the safest country in the world: crime rate here is lower than in the Vatican City.

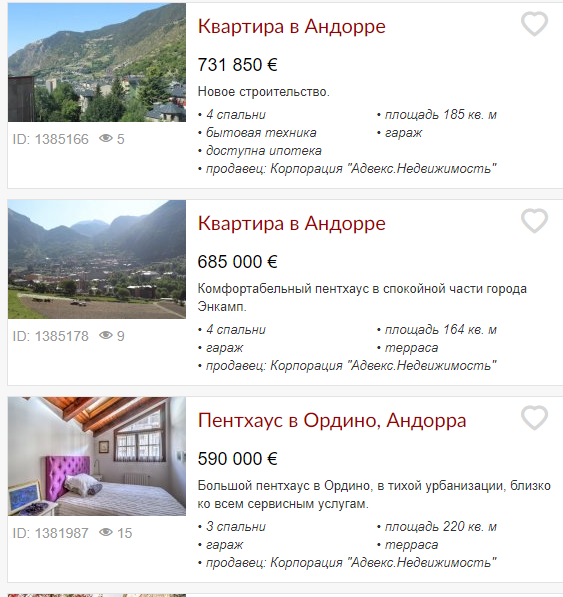

Naumeyko left with his whole family, having acquired housing for all its members. The country is small but very popular with people who want to start life from scratch. This, however, comes at a price. A residence permit can be acquired only on the condition that one has bought real estate for a minimum of 400,000 euros for each resident and additionally opened an account in a local bank for a significant amount of money. Such expenses were not really in line with Naumeyko’s official salary.

Even an apartment will set you back about a hundred million rubles. Mortgages are not issued to non-residents who have to acquire real estate with a single payment — by cash only.

There is an interesting tidbit, too: back in December 2006, the ex-Gazpromian turned Andorran citizen issued a 15 million euro loan to his friends, a Panamian business partnership Marietta LTD. This fact has been revealed only recently, when Anatoly Naumeyko filed a 28.5 million euro lawsuit to a EU court against his son Sergey, head of an Estonian company Merona Kinnisvara. The lawsuit, experts say, is fictitious and bears signs of a money laundering scheme through a number of companies owned by relatives. The property had been previously seized by the Geneva Arbitration Court. One might think these were family matters. The father could have quarreled with his son and demanded the pretty penny donated for his business development. But maybe the deal had been fictitious from the start, and the newly-minted Andorran citizen (while remaining head of the Gazprom structure for another three years) had simply been moving “a little something” for his young one from his own secret piggy bank. What’s important for us is the mere size of amounts in question which we did not even have the courage to convert into the ruble equivalent.

What is the point of suing yourself or your blood relative, you may ask? Well, rich people have the strangest habits. And money laundering schemes. The thing is, all of Europe continues to live according to Roman law, in which a court decision has the highest power and cannot be challenged. It does not matter how the trial ends and who will pay: the son or the father. What matters is that the court has already registered the sum and this money now looks legit.

This scheme has been used for a long time, in numerous variations. First a front company is created. Then a cash deposit is made on behalf of any person (even an anonymous one) that is finally withdrawn for investment in a legitimate business.

The money laundering process usually has the following pattern:

1. Placement. Criminals put dirty money into legal financial institutions in the form of cash bank deposits or loans from individuals.

2. Layering. By means of electronic transactions money is transferred between different accounts, converted into a different currency, and then used to purchase expensive goods in order to change the monetary form.

3. Integration. This is the final stage at which laundered money is introduced into economy as legal by way of bank transfers to the accounts of companies used for laundering, or by way of selling expensive goods that were purchased during the second stage.

4. It also possible, as in Naumeyko’s case, to win this money by court action after it had passed through several accounts — as if a loan was not repaid.

It is highly probable that the amounts of money that Anatoly Naumeyko and his family members legalized in Europe had been received in an unfair and illegal way. As experience shows, EU countries are sensitive to the origin of funds that flow into the economy of the Commonwealth. It is therefore fair to assume that the odyssey of this former Gazprom official’s fortune in Europe is only just beginning and that Anatoly Naumeyko has yet to give explanations about the sources of his capital.

To be continued.

Газпром - национальное достояние? http://glagolurfo.com/newsitems/2019/9/9/gazprom---nacionalnoe-dostoyanie/

¿Gazprom es un Patrimonio Nacional? http://glagolurfo.com/newsitems/2019/9/27/gazprom-es-un-patrimonio-nacional/